what were many of the stained glass windows of the middle ages meant to do

The due north rose window of the Chartres Cathedral (Chartres, France), donated by Blanche of Castile. Information technology represents the Virgin Mary as Queen of Heaven, surrounded by Biblical kings and prophets. Below is St Anne, mother of the Virgin, with iv righteous leaders. The window includes the arms of France and Castile

The term stained glass refers either to coloured glass as a material or to works created from information technology. Throughout its thousand-year history, the term has been practical nigh exclusively to the windows of churches and other significant religious buildings. Although traditionally fabricated in flat panels and used equally windows, the creations of modern stained drinking glass artists too include three-dimensional structures and sculpture. Mod vernacular usage has oft extended the term "stained glass" to include domestic atomic number 82 calorie-free and objets d'art created from foil glasswork exemplified in the famous lamps of Louis Condolement Tiffany.

Equally a fabric stained glass is glass that has been coloured by adding metallic salts during its manufacture, and usually and so farther decorating it in various ways. The coloured glass is crafted into stained drinking glass windows in which small pieces of drinking glass are arranged to course patterns or pictures, held together (traditionally) past strips of pb and supported by a rigid frame. Painted details and yellow stain are oftentimes used to heighten the design. The term stained glass is as well applied to windows in enamelled glass in which the colours take been painted onto the glass and so fused to the drinking glass in a kiln; very often this technique is only applied to parts of a window.

Renaissance roundel, inserted into a plain glass window, using but black or chocolate-brown drinking glass pigment, and silver stain in a range of yellows and gold. The local bishop-saint Lambrecht of Maastricht stands in an extensive landscape, 1510–twenty. The diameter is 8+ 3⁄iv in (22 cm), and the piece was designed to be placed depression, close to the viewer, very possibly not in a church.

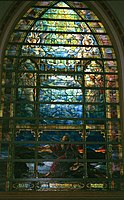

Stained drinking glass, every bit an art and a craft, requires the artistic skill to conceive an appropriate and workable pattern, and the engineering skills to assemble the slice. A window must fit snugly into the space for which it is made, must resist wind and rain, and also, specially in the larger windows, must support its own weight. Many large windows have withstood the exam of time and remained substantially intact since the Late Middle Ages. In Western Europe, together with illuminated manuscripts, they constitute the major course of medieval pictorial art to have survived. In this context, the purpose of a stained glass window is not to allow those within a building to see the world exterior or even primarily to acknowledge light but rather to control it. For this reason stained glass windows have been described as "illuminated wall decorations".

The blueprint of a window may exist abstract or figurative; may incorporate narratives drawn from the Bible, history, or literature; may represent saints or patrons, or use symbolic motifs, in detail armorial. Windows inside a edifice may be thematic, for example: inside a church – episodes from the life of Christ; within a parliament building – shields of the constituencies; within a college hall – figures representing the arts and sciences; or within a dwelling house – flora, beast, or mural.

Glass production [edit]

During the late medieval period, drinking glass factories were gear up up where there was a ready supply of silica, the essential fabric for glass industry. Silica requires a very high temperature to cook, something non all glass factories were able to achieve. Such materials as potash, soda, and lead can be added to lower the melting temperature. Other substances, such as lime, are added to rebuild the weakened network and make the glass more stable. Drinking glass is coloured past adding metallic oxide powders or finely divided metals while it is in a molten state.[1] Copper oxides produce dark-green or blueish green, cobalt makes deep blue, and golden produces vino ruby-red and violet glass. Much of modernistic red glass is produced using copper, which is less expensive than aureate and gives a brighter, more vermilion shade of ruddy. Drinking glass coloured while in the clay pot in the furnace is known as pot metal glass, as opposed to flashed glass.

Cylinder glass or Muff [edit]

Using a blow-piping, a "gather" (glob) of molten glass is taken from the pot heating in the furnace. The gather is formed to the correct shape and a bubble of air blown into it. Using metal tools, molds of woods that accept been soaking in h2o, and gravity, the gather is manipulated to course a long, cylindrical shape. As information technology cools, information technology is reheated so that the manipulation can go along. During the procedure, the lesser of the cylinder is removed. One time brought to the desired size it is left to cool. I side of the cylinder is opened. Information technology is put into another oven to quickly heat and flatten information technology, and then placed in an annealer to cool at a controlled rate, making the material more than stable. "Hand-diddled" cylinder (too called muff glass) and crown glass were the types used in aboriginal stained-glass windows. Stained glass windows were commonly in churches and chapels besides every bit many more well respected buildings.

Crown drinking glass [edit]

This mitt-blown glass is created past blowing a chimera of air into a gather of molten glass and and then spinning it, either by paw or on a table that revolves apace like a potter's bike. The centrifugal forcefulness causes the molten bubble to open upwards and flatten. Information technology tin can then exist cutting into small-scale sheets. Glass formed this way tin be either coloured and used for stained-glass windows, or uncoloured as seen in pocket-size paned windows in 16th- and 17th-century houses. Concentric, curving waves are feature of the process. The center of each piece of glass, known as the "bull's-heart", is subject to less acceleration during spinning, so information technology remains thicker than the balance of the sheet. It as well has the pontil mark, a distinctive lump of drinking glass left past the "pontil" rod, which holds the glass as it is spun out. This lumpy, refractive quality means the bulls-eyes are less transparent, simply they have notwithstanding been used for windows, both domestic and ecclesiastical. Crown drinking glass is still made today, but non on a big scale.

Rolled glass [edit]

Rolled glass (sometimes called "table drinking glass") is produced past pouring molten glass onto a metallic or graphite tabular array and immediately rolling it into a sheet using a large metal cylinder, like to rolling out a pie chaff. The rolling can be done by paw or by machine. Glass can be "double rolled", which means it is passed through two cylinders at one time (similar to the clothes wringers on older washing machines) to yield drinking glass of a specified thickness (typically about one/8" or 3mm). The drinking glass is and so annealed. Rolled glass was first commercially produced effectually the mid-1830s and is widely used today. It is oft called cathedral drinking glass, but this has nothing to do with medieval cathedrals, where the glass used was hand-blown.

Flashed glass [edit]

Architectural glass must exist at least i / 8 of an inch (3 mm) thick to survive the button and pull of typical wind loads. However, in the cosmos of red glass, the colouring ingredients must be of a sure concentration, or the colour volition not develop. This results in a color so intense that at the thickness of ane / eight inch (3 mm), the blood-red glass transmits footling calorie-free and appears black. The method employed is to laminate a thin layer of blood-red glass to a thicker body of glass that is articulate or lightly tinted, forming "flashed drinking glass".

A lightly coloured molten assemble is dipped into a pot of molten cherry-red glass, which is and so blown into a sail of laminated glass using either the cylinder (muff) or the crown technique described above. Once this method was found for making red glass, other colours were made this way as well. A smashing advantage is that the double-layered glass can be engraved or abraded to reveal the clear or tinted glass below. The method allows rich detailing and patterns to be accomplished without needing to add more pb-lines, giving artists greater freedom in their designs. A number of artists have embraced the possibilities flashed drinking glass gives them. For instance, 16th-century heraldic windows relied heavily on a diversity of flashed colours for their intricate crests and creatures. In the medieval period the glass was abraded; later, hydrofluoric acrid was used to remove the flash in a chemical reaction (a very dangerous technique), and in the 19th century sandblasting started to exist used for this purpose.

Modern production of traditional glass [edit]

There are a number of glass factories, notably in Germany, the The states, England, France, Poland and Russia, which produce high-quality glass, both hand-diddled (cylinder, muff, crown) and rolled (cathedral and opalescent). Modern stained-glass artists have a number of resources to utilise and the work of centuries of other artists from which to learn as they continue the tradition in new ways. In the late 19th and 20th centuries there have been many innovations in techniques and in the types of glass used. Many new types of glass take been developed for use in stained glass windows, in particular Tiffany drinking glass and Dalle de verre.

Colours [edit]

Role of German panel of 1444 with the Visitation; pot metallic of various colours, including white glass, blackness vitreous paint, yellow silver stain, and the "olive-green" parts are enamel. The plant patterns in the cherry sky are formed past scratching away black paint from the red drinking glass before firing. A restored panel with new lead cames.

"Pot metallic" and flashed glass [edit]

The primary method of including colour in stained glass is to utilise glass, originally colourless, that has been given colouring by mixing with metallic oxides in its melted state (in a crucible or "pot"), producing glass sheets that are coloured all the style through; these are known equally "pot metal" glass.[2] A second method, sometimes used in some areas of windows, is flashed glass, a sparse coating of coloured glass fused to colourless glass (or coloured glass, to produce a unlike colour). In medieval glass flashing was particularly used for reds, every bit glass made with aureate compounds was very expensive and tended to exist besides deep in color to use at full thickness.[3]

Glass pigment [edit]

Another group of techniques give additional colouring, including lines and shading, by treating the surfaces of the coloured sheets, and often fixing these effects by a light firing in a furnace or kiln. These methods may be used over wide areas, especially with silver stain, which gave amend yellows than other methods in the Middle Ages. Alternatively they may exist used for painting linear effects, or polychrome areas of detail. The most common method of adding the blackness linear painting necessary to ascertain stained glass images is the use of what is variously called "glass paint", "vitreous pigment", or "grisaille paint". This was practical as a mixture of powdered glass, fe or rust filings to give a black color, clay, and oil, vinegar or water for a brushable texture, with a folder such as glue arabic. This was painted on the pieces of coloured glass, then fired to burn away the ingredients giving texture, leaving a layer of the glass and colouring, fused to the main glass piece.[4]

High german glass, Nuremberg, after a cartoon past Sebald Beham, c. 1525. Argent stain produces a range of yellows and gold, and painted on the contrary of the blue sky, gives the dark green of the cross.[5]

Silver stain [edit]

"Silver stain", introduced shortly afterward 1300, produced a wide range of yellow to orange colours; this is the "stain" in the term "stained glass". Silver compounds (notably silver nitrate)[half-dozen] are mixed with bounden substances, applied to the surface of glass, and then fired in a furnace or kiln.[7] They can produce a range of colours from orange-red to yellowish. Used on blue glass they produce greens. The manner the glass is heated and cooled can significantly impact the colours produced past these compounds. The chemical science involved is circuitous and not well understood. The chemicals actually penetrate the glass they are added to a little manner, and the technique therefore gives extremely stable results. By the 15th century it had go cheaper than using pot metal glass and was frequently used with drinking glass paint as the only colour on transparent drinking glass.[8] Silvery stain was practical to the contrary face up of the drinking glass to silvery pigment, as the two techniques did not work well one on peak of the other. The stain was usually on the outside face up, where information technology appears to take given the glass some protection against weathering, although this can too be truthful for paint. They were too probably fired separately, the stain needing a lower heat than the paint.[9]

"Sanguine" or "Cousin's rose" [edit]

"Sanguine", "carnation", "Rouge Jean Cousin" or "Cousin's rose", afterwards its supposed inventor,[10] is an iron-based fired paint producing red colours, mainly used to highlight small areas, often on mankind. It was introduced around 1500.[xi] Copper stain, like to silver stain but using copper compounds, too produced reds, and was mainly used in the 18th and 19th centuries.[12]

Common cold painting [edit]

"Common cold pigment" is various types of pigment that were practical without firing. Contrary to the optimistic claims of the 12th century writer Theophilus Presbyter, cold pigment is not very durable, and very niggling medieval paint has survived.[12]

Scratching techniques [edit]

Equally well as painting, scratched sgraffito techniques were often used. This involved painting a colour over pot metallic glass of another colour, and so before firing selectively scratching the glass paint away to make the design, or the lettering of an inscription. This was the most common method of making inscriptions in early on medieval drinking glass, giving white or light messages on a blackness background, with later inscriptions more oftentimes using black painted letters on a transparent glass background.[13]

"Pot drinking glass" colours [edit]

These are the colours in which the drinking glass itself is made, every bit opposed to colours practical to the glass.

Transparent glass [edit]

Ordinary soda-lime glass appears colourless to the naked heart when it is sparse, although iron oxide impurities produce a greenish tint which becomes evident in thick pieces or with the aid of scientific instruments. A number of additives are used to reduce the green tint, particularly if the glass is to be used for plain window glass, rather than stained glass windows. These additives include manganese dioxide which produces sodium permanganate, and may result in a slightly mauve tint, characteristic of the glass in older houses in New England. Selenium has been used for the aforementioned purpose.[14]

Green glass [edit]

While very pale light-green is the typical color of transparent drinking glass, deeper greens can exist achieved by the addition of Iron(Ii) oxide which results in a blueish-green drinking glass. Together with chromium it gives glass of a richer green colour, typical of the drinking glass used to brand wine bottles. The add-on of chromium yields dark green glass, suitable for flashed glass.[15] Together with tin can oxide[ clarification needed ] and arsenic information technology yields emerald green glass.

Blue glass [edit]

- In medieval times, bluish glass was made by adding cobalt blue, which at a concentration of 0.025% to 0.1% in soda-lime drinking glass achieves the brilliant blue characteristic of Chartres Cathedral.

- The addition of sulphur to boron-rich borosilicate glasses imparts a blue colour.

- The addition of copper oxide at two–3% produces a turquoise color.

- The addition of nickel, at different concentrations, produces blue, violet, or blackness drinking glass.[16]

Red glass [edit]

- Metal gilt, in very depression concentrations (around 0.001%), produces a rich cherry-coloured glass ("crimson aureate"); in even lower concentrations information technology produces a less intense red, often marketed equally "cranberry glass". The colour is caused past the size and dispersion of aureate particles. Reddish aureate drinking glass is usually fabricated of lead glass with can added.

- Pure metallic copper produces a very dark cherry-red, opaque glass. Drinking glass created in this way is generally "flashed" (laminated glass). It was used extensively in the tardily 19th and early 20th centuries and exploited for the decorative effects that could be achieved by sanding and engraving.

- Selenium is an important agent to make pink and red drinking glass. When used together with cadmium sulphide, information technology yields a vivid red color known every bit "Selenium Ruby-red".[14]

Xanthous glass [edit]

- This was very often achieved by "silver stain" practical externally to the sheets of glass (see above).

- The addition of sulphur, together with carbon and iron salts, is used to class iron polysulphides and produce amber glass ranging from yellowish to virtually black. With calcium it yields a deep yellow colour.[17]

- Calculation titanium produces yellowish-brownish glass. Titanium is rarely used on its own and is more oftentimes employed to intensify and brighten other additives.

- Cadmium together with sulphur results in deep xanthous color, ofttimes used in glazes. Even so, cadmium is toxic.

- Uranium (0.one% to 2%) can be added to give glass a fluorescent yellow or greenish colour.[18] Uranium glass is typically not radioactive plenty to be unsafe, but if basis into a powder, such as by polishing with sandpaper, and inhaled, it can be carcinogenic. When used with lead glass with a very loftier proportion of lead, it produces a deep red colour.

Purple glass [edit]

- The addition of manganese gives an amethyst colour. Manganese is ane of the oldest glass additives, and imperial manganese drinking glass has been used since early Egyptian history.

- Nickel, depending on the concentration, produces blue, or violet, or even black glass.[xvi] Pb crystal with added nickel acquires a purplish colour.

White glass [edit]

- Tin can dioxide with antimony and arsenic oxides produce an opaque white glass, first used in Venice to produce an imitation porcelain. White glass was used extensively by Louis Comfort Tiffany to create a range of opalescent, mottled and streaky glasses.

-

13th-century window from Chartres showing extensive use of the ubiquitous cobalt bluish with green and purple-brown glass, details of amber and borders of flashed red glass.

-

A 19th-century window illustrates the range of colours common in both Medieval and Gothic Revival glass, Lucien Begule, Lyon (1896)

-

A 16th-century window by Arnold of Nijmegen showing the combination of painted drinking glass and intense colour common in Renaissance windows

-

A late 20th-century window showing a graded range of colours. Ronald Whiting, Chapel Studios. Tattershall Castle, United kingdom

-

A window by Tiffany illustrating the evolution and use of multi-coloured flashed, opalised and streaky glasses at the stop of the 19th century

Creating stained-glass windows [edit]

Swiss armourial glass of the Arms of Unterwalden, 1564, with typical painted details, extensive silver stain, Cousin's rose on the face, and flashed ruby glass with abraded white motif

Design [edit]

The outset phase in the product of a window is to brand, or learn from the architect or owners of the building, an accurate template of the window opening that the glass is to fit.

The subject area matter of the window is determined to suit the location, a item theme, or the wishes of the patron. A small design chosen a Vidimus (from Latin "nosotros have seen") is prepared which can be shown to the patron. A scaled model maquette may as well be provided. The designer must accept into account the blueprint, the structure of the window, the nature and size of the glass available and his or her ain preferred technique.

A traditional narrative window has panels which relate a story. A figurative window could have rows of saints or dignitaries. Scriptural texts or mottoes are sometimes included and perhaps the names of the patrons or the person to whose memory the window is defended. In a window of a traditional blazon, it is usually left to the discretion of the designer to fill up the surrounding areas with borders, floral motifs and canopies.

A full-sized drawing is fatigued for every "low-cal" (opening) of the window. A small church window might typically have 2 lights, with some simple tracery lights above. A big window might accept four or v lights. The due east or w window of a large cathedral might take seven lights in iii tiers, with elaborate tracery. In medieval times the cartoon was fatigued directly on the surface of a whitewashed tabular array, which was then used as a pattern for cutting, painting and assembling the window. The cartoon is so divided into a patchwork, providing a template for each small drinking glass slice. The exact position of the atomic number 82 which holds the glass in place is besides noted, as it is part of the calculated visual consequence.

Selecting and painting the glass [edit]

Each piece of glass is selected for the desired colour and cutting to lucifer a section of the template. An exact fit is ensured by "grozing" the edges with a tool which can nibble off minor pieces. Details of faces, hair and hands can be painted onto the inner surface of the glass using a special glass paint which contains finely ground lead or copper filings, ground glass, gum arabic and a medium such as vino, vinegar or (traditionally) urine. The art of painting details became increasingly elaborate and reached its acme in the early 20th century.

From 1300 onwards, artists started using "silvery stain" which was made with silver nitrate. It gave a yellow effect ranging from pale lemon to deep orange. Information technology was usually painted onto the outside of a slice of drinking glass, and then fired to make information technology permanent. This yellow was particularly useful for enhancing borders, canopies and haloes, and turning blue glass into green drinking glass. Past about 1450, a stain known as "Cousin's rose" was used to raise mankind tones.

In the 16th century, a range of glass stains were introduced, virtually of them coloured by ground glass particles. They were a form of enamelled glass. Painting on glass with these stains was initially used for small heraldic designs and other details. By the 17th century a style of stained glass had evolved that was no longer dependent upon the skilful cutting of coloured glass into sections. Scenes were painted onto drinking glass panels of square format, similar tiles. The colours were so annealed to the glass before the pieces were assembled.

A method used for embellishment and gilding is the decoration of one side of each of two pieces of thin glass, which are then placed back to dorsum within the pb came. This allows for the use of techniques such as Angel gilding and Eglomise to produce an effect visible from both sides but non exposing the busy surface to the atmosphere or mechanical harm.

Assembly and mounting [edit]

Once the glass is cutting and painted, the pieces are assembled by slotting them into H-sectioned atomic number 82 cames. All the joints are then soldered together and the glass pieces are prevented from rattling and the window made weatherproof past forcing a soft oily cement or mastic between the glass and the cames. In modern windows, copper foil is now sometimes used instead of lead.[xix] For further technical details, see Came glasswork.

Traditionally, when a window was inserted into the window space, iron rods were put across it at various points to support its weight. The window was tied to these rods with copper wire. Some very large early Gothic windows are divided into sections past heavy metal frames chosen ferramenta. This method of back up was too favoured for large, usually painted, windows of the Baroque catamenia.

- Technical details

-

Thomas Becket window from Canterbury showing the pot metal and painted glass, lead H-sectioned cames, modern steel rods and copper wire attachments

-

Detail from a 19th or 20th-century window in Eyneburg, Belgium, showing detailed polychrome painting of face.

History [edit]

Origins [edit]

Coloured glass has been produced since aboriginal times. Both the Egyptians and the Romans excelled at the manufacture of small colored drinking glass objects. Phoenicia was important in glass manufacture with its chief centres Sidon, Tyre and Antioch. The British Museum holds two of the finest Roman pieces, the Lycurgus Cup, which is a murky mustard color but glows purple-ruddy to transmitted light, and the cameo glass Portland vase which is midnight blue, with a carved white overlay.

In early on Christian churches of the 4th and 5th centuries, in that location are many remaining windows which are filled with ornate patterns of thinly-sliced alabaster ready into wooden frames, giving a stained-drinking glass similar effect.

Prove of stained-glass windows in churches and monasteries in Great britain tin can be found as early equally the 7th century. The earliest known reference dates from 675 Advertizement when Benedict Biscop imported workmen from France to glaze the windows of the monastery of St Peter which he was building at Monkwearmouth. Hundreds of pieces of coloured glass and pb, dating dorsum to the late 7th century, have been discovered here and at Jarrow.[twenty]

In the Middle East, the glass industry of Syria continued during the Islamic period with major centres of manufacture at Raqqa, Aleppo and Damascus and the most important products being highly transparent colourless drinking glass and golden glass, rather than coloured glass.

-

A perfume flask from 100 BC to 200 Advertising

In Southwest Asia [edit]

The cosmos of stained glass in Southwest Asia began in ancient times. One of the region's earliest surviving formulations for the production of colored glass comes from the Assyrian city of Nineveh, dating to the seventh century BC. The Kitab al-Durra al-Maknuna, attributed to the 8th century alchemist Jābir ibn Hayyān, discusses the production of colored glass in ancient Babylon and Egypt. The Kitab al-Durra al-Maknuna besides describes how to create colored drinking glass and artificial gemstones fabricated from high-quality stained glass.[21] The tradition of stained glass manufacture has continued, with mosques, palaces, and public spaces being decorated with stained glass throughout the Islamic globe. The stained drinking glass of Islam is more often than not non-pictorial and of purely geometric design, only may contain both floral motifs and text.

-

All-encompassing stained glasses of Nasir-ol-Molk Mosque in Shiraz, Islamic republic of iran and the light passing through them

-

Stained glass in Dowlat Abad Garden at Yazd, Islamic republic of iran

-

From a mosque in Jerusalem, this window contains highly detailed text.

Medieval glass in Europe [edit]

Stained glass, as an fine art form, reached its peak in the Middle Ages when information technology became a major pictorial course used to illustrate the narratives of the Bible to a largely illiterate populace.

In the Romanesque and Early on Gothic flow, from about 950 to 1240, the untraceried windows demanded large expanses of glass which of necessity were supported by robust atomic number 26 frames, such as may be seen at Chartres Cathedral and at the eastern end of Canterbury Cathedral. As Gothic compages developed into a more ornate form, windows grew larger, affording greater illumination to the interiors, but were divided into sections by vertical shafts and tracery of stone. This elaboration of form reached its summit of complexity in the Flamboyant style in Europe, and windows grew however larger with the development of the Perpendicular manner in England and Rayonnant style in France.

Integrated with the lofty verticals of Gothic cathedrals and parish churches, drinking glass designs became more than daring. The round form, or rose window, developed in France from relatively elementary windows with openings pierced through slabs of thin stone to bike windows, as exemplified by the west front of Chartres Cathedral, and ultimately to designs of enormous complexity, the tracery being drafted from hundreds of different points, such as those at Sainte-Chapelle, Paris and the "Bishop's Centre" at Lincoln Cathedral.

While stained glass was widely manufactured, Chartres was the greatest centre of stained drinking glass industry, producing glass of unrivalled quality.[22]

- Medieval drinking glass in France

-

-

-

The Due south Transept windows from Chartres Cathedral

- Medieval glass in Germany and Austria

-

King David from Augsburg Cathedral, early on 12th century. One of the oldest examples in situ.

-

Crucifixion with Ss Catherine, George and Margaret, Leechkirche, Graz, Austria

-

The Crucifixion and Virgin and Kid in Majesty, Cologne Cathedral, (1340)

- Medieval drinking glass in England

-

Detail of a Tree of Jesse from York Minster (c. 1170), the oldest stained-glass window in England.

-

-

The Concluding Judgement, St Mary's Church, Fairford, (1500–17) by Barnard Blossom[23]

- Medieval glass in Espana

Renaissance, Reformation and Classical windows [edit]

Probably the primeval scheme of stained glass windows that was created during the Renaissance was that for Florence Cathedral, devised past Lorenzo Ghiberti.[24] The scheme includes three ocular windows for the dome and three for the facade which were designed from 1405 to 1445 by several of the about renowned artists of this period: Ghiberti, Donatello, Uccello and Andrea del Castagno. Each major ocular window contains a single pic fatigued from the Life of Christ or the Life of the Virgin Mary, surrounded by a wide floral edge, with two smaller facade windows by Ghiberti showing the martyred deacons, St Stephen and St Lawrence. Ane of the cupola windows has since been lost, and that by Donatello has lost nearly all of its painted details.[24]

In Europe, stained drinking glass continued to be produced; the manner evolved from the Gothic to the Classical, which is well represented in Deutschland, Belgium and the netherlands, despite the ascent of Protestantism. In France, much glass of this period was produced at the Limoges factory, and in Italy at Murano, where stained glass and faceted lead crystal are oft coupled together in the same window. The French Revolution brought about the fail or destruction of many windows in France.

At the Reformation in England, big numbers of medieval and Renaissance windows were smashed and replaced with plain drinking glass. The Dissolution of the Monasteries under Henry Eight and the injunctions of Thomas Cromwell against "abused images" (the object of veneration) resulted in the loss of thousands of windows. Few remain undamaged; of these the windows in the private chapel at Hengrave Hall in Suffolk are amidst the finest. With the latter wave of devastation the traditional methods of working with stained glass died, and were non rediscovered in England until the early 19th century. See Stained glass – British glass, 1811–1918 for more details.

In the Netherlands a rare scheme of glass has remained intact at Grote Sint-Jan Church, Gouda. The windows, some of which are 18 metres (59 anxiety) high, date from 1555 to the early 1600s; the earliest is the work of Dirck Crabeth and his brother Wouter. Many of the original cartoons still exist.[25]

-

The Triumph of Freedom of Conscience, Sint Janskerk, maker Adriaen Gerritszoon de Vrije (Gouda); design Joachim Wtewael (Utrecht) (1595–1600)

-

Domestic window by Dirck Crabeth for the house of Adriaen Dircxzoon van Crimpen of Leiden. (1543) The windows bear witness scenes from the lives of the Prophet Samuel and the Campaigner Paul. Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris.[25]

-

Glass painting depicting Mordnacht (murder night) on 23/24 February 1350 and heraldry of the commencement Meisen guild's Zunfthaus, Zürich. (c. 1650)

-

-

Auch Cathedral (France), Renaissance stained glass by Arnaud de Moles (detail), 1507–1513).

Revival in Britain [edit]

The Catholic revival in England, gaining force in the early 19th century with its renewed interest in the medieval church, brought a revival of church building in the Gothic fashion, claimed by John Ruskin to exist "the true Catholic style". The architectural motility was led by Augustus Welby Pugin. Many new churches were planted in big towns and many old churches were restored. This brought about a great demand for the revival of the art of stained glass window making.

Amongst the primeval 19th-century English manufacturers and designers were William Warrington and John Hardman of Birmingham, whose nephew, John Hardman Powell, had a commercial eye and exhibited works at the Philadelphia Exhibition of 1876, influencing stained glass in the United states of america of America. Other manufacturers included William Wailes, Ward and Hughes, Clayton and Bell, Heaton, Butler and Bayne and Charles Eamer Kempe. A Scottish designer, Daniel Cottier, opened firms in Australia and the United states of america.

-

1 of England's largest windows, the due east window of Lincoln Cathedral, Ward and Nixon (1855), is a formal system of small narrative scenes in roundels

-

William Wailes. This window has the vivid pastel color, wealth of inventive ornamentation, and stereotypical gestures of windows by this firm. St Mary's, Chilham

-

South aisle east window of St. Mary Redcliffe Bristol by Clayton and Bong, 1861.

Revival in France [edit]

In French republic at that place was a greater continuity of stained glass product than in England. In the early 19th century most stained glass was made of large panes that were extensively painted and fired, the designs often being copied directly from oil paintings past famous artists. In 1824 the Sèvres porcelain manufacturing plant began producing stained glass to supply the increasing demand. In France many churches and cathedrals suffered despoliation during the French Revolution. During the 19th century a great number of churches were restored by Viollet-le-Duc. Many of France'due south finest ancient windows were restored at that time. From 1839 onwards much stained glass was produced that very closely imitated medieval glass, both in the artwork and in the nature of the glass itself. The pioneers were Henri Gèrente and André Lusson.[26] Other glass was designed in a more Classical manner, and characterised by the brilliant cerulean color of the blue backgrounds (every bit against the purple-blue of the glass of Chartres) and the utilise of pink and mauve glass.

-

Detail of a "Tree of Jesse" window in Reims Cathedral designed in the 13th-century way by L. Steiheil and painted by Coffetier for Viollet-le-Duc, (1861)

-

St Louis administering Justice by Lobin in the painterly manner. (19th century) Church building of St Medard, Thouars.

Revival [edit]

During the mid- to tardily 19th century, many of Germany's ancient buildings were restored, and some, such as Cologne Cathedral, were completed in the medieval style. At that place was a great need for stained glass. The designs for many windows were based directly on the work of famous engravers such as Albrecht Dürer. Original designs often imitate this style. Much 19th-century German drinking glass has big sections of painted detail rather than outlines and details dependent on the lead. The Royal Bavarian Glass Painting Studio was founded by Ludwig I in 1827.[26] A major house was Mayer of Munich, which commenced drinking glass product in 1860, and is still operating equally Franz Mayer of Munich, Inc.. High german stained drinking glass found a market across Europe, in America and Commonwealth of australia. Stained glass studios were also founded in Italia and Belgium at this time.[26]

In the Austrian Empire and later Austria-hungary, ane of the leading stained drinking glass artists was Carl Geyling, who founded his studio in 1841. His son would continue the tradition as Carl Geyling's Erben, which still exists today. Carl Geyling'due south Erben completed numerous stained glass windows for major churches in Vienna and elsewhere, and received an Imperial and Royal Warrant of Appointment from emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria.

Innovations in Britain and Europe [edit]

Among the most innovative English designers were the Pre-Raphaelites, William Morris (1834–1898) and Edward Burne-Jones (1833–1898), whose work heralds the influential Arts and Crafts Movement, which regenerated stained glass throughout the English-speaking earth. Amid its most important exponents in England was Christopher Whall (1849-1924), author of the classic craft transmission 'Stained Glass Work' (published London and New York, 1905), who advocated the direct interest of designers in the making of their windows. His masterpiece is the series of windows (1898-1910) in the Lady Chapel at Gloucester Cathedral. Whall taught at London'southward Royal Higher of Art and Central School of Arts and Crafts: his many pupils and followers included Karl Parsons, Mary Lowndes, Henry Payne, Caroline Townshend, Veronica Whall (his daughter) and Paul Woodroffe.[27] The Scottish creative person Douglas Strachan (1875-1950), who was much influenced past Whall's instance, adult the Arts & Crafts idiom in an expressionist way, in which powerful imagery and meticulous technique are masterfully combined. In Republic of ireland, a generation of young artists taught by Whall'southward pupil Alfred Child at Dublin'due south Metropolitan School of Fine art created a distinctive national school of stained glass: its leading representatives were Wilhelmina Geddes, Michael Healy and Harry Clarke.

Art Nouveau or Belle Epoque stained drinking glass pattern flourished in France, and Eastern Europe, where it can be identified by the use of curving, sinuous lines in the lead, and swirling motifs. In France information technology is seen in the work of Francis Chigot of Limoges. In Uk information technology appears in the refined and formal leadlight designs of Charles Rennie Mackintosh.

-

David's charge to Solomon shows the strongly linear design and use of flashed glass for which Burne-Jones' designs are famous. Trinity Church, Boston, US, (1882)

-

God the Creator past Stanisław Wyspiański, this window has no drinking glass painting, just relies entirely on leadlines and skilful placement of colour and tone. Franciscan Church building, Kraków (c. 1900)

-

Art Nouveau by Jacques Grüber, the glass harmonising with the curving architectural forms that surround it, Musée de 50'École de Nancy (1904).

Innovations in the Usa [edit]

J&R Lamb Studios, established in 1857 in New York City, was the first major decorative arts studio in the United states of america and for many years a major producer of ecclesiastical stained glass.

Notable American practitioners include John La Farge (1835–1910), who invented opalescent glass and for which he received a U.S. patent on 24 February 1880, and Louis Comfort Tiffany (1848–1933), who received several patents for variations of the aforementioned opalescent process in November of the aforementioned yr and he used the copper foil method as an alternative to lead in some windows, lamps and other decorations. Sanford Bray of Boston patented the utilize of copper foil in stained drinking glass in 1886,[28] Withal, a reaction against the aesthetics and technique of opalescent windows - led initially by architects such equally Ralph Adams Cram - led to a rediscovery of traditional stained glass in the early on 1900s. Charles J. Connick (1875-1945), who founded his Boston studio in 1913, was greatly influenced by his study of medieval stained drinking glass in Europe and by the Arts & Crafts philosophy of Englishman Christopher Whall. Connick created hundreds of windows throughout the US, including major glazing schemes at Princeton Academy Chapel (1927-9) and at Pittsburgh'due south Heinz Memorial Chapel (1937-viii).[27] Other American artist-makers who espoused a medieval-inspired idiom included Nicola D'Ascenzo of Philadelphia, Wilbur Burnham and Reynolds, Francis & Rohnstock of Boston and Henry Wynd Immature and J. Gordon Guthrie of New York.

-

John La Farge, The Affections of Help, North Easton, MA shows the use of tiny panes contrasting with large areas of opalescent glass. Window restored past Victor Rothman Stained Glass, Yonkers NY

-

Religion Enthroned, J&R Lamb Studios, designer Frederick Stymetz Lamb, c. 1900. Brooklyn Museum. Symmetrical design, "Aesthetic Style", a limited palette and extensive use of mottled glass.

-

The Holy City by Louis Comfort Tiffany (1905). This 58-console window has brilliant blood-red, orange, and yellow etched glass for the sunrise, with textured glass used to create the effect of moving water.

-

20th and 21st centuries [edit]

Many 19th-century firms failed early in the 20th century every bit the Gothic movement was superseded by newer styles. At the same time there were also some interesting developments where stained glass artists took studios in shared facilities. Examples include the Glass House in London fix by Mary Lowndes and Alfred J. Drury and An Túr Gloine in Dublin, which was run by Sarah Purser and included artists such as Harry Clarke.

A revival occurred in the eye of the century because of a desire to restore thousands of church windows throughout Europe destroyed as a result of World State of war 2 bombing. German artists led the way. Much piece of work of the menstruation is mundane and often was non made past its designers, but industrially produced.

Other artists sought to transform an aboriginal art class into a contemporary one, sometimes using traditional techniques while exploiting the medium of glass in innovative ways and in combination with different materials. The use of slab glass, a technique known equally Dalle de Verre, where the glass is set up in physical or epoxy resin, was a 20th-century innovation credited to Jean Gaudin and brought to the United kingdom by Pierre Fourmaintraux. One of the most prolific glass artists using this technique was the Dominican Friar Dom Charles Norris OSB of Buckfast Abbey.

Gemmail, a technique developed by the French artist Jean Crotti in 1936 and perfected in the 1950s, is a type of stained glass where adjacent pieces of drinking glass are overlapped without using lead cames to join the pieces, assuasive for greater diverseness and subtlety of color.[29] [30] Many famous works by late 19th- and early 20th-century painters, notably Picasso, have been reproduced in gemmail.[31] A major exponent of this technique is the High german artist Walter Womacka.

Amidst the early well-known 20th-century artists who experimented with stained glass as an Abstract art course were Theo van Doesburg and Piet Mondrian. In the 1960s and 1970s the Expressionist painter Marc Chagall produced designs for many stained glass windows that are intensely coloured and crammed with symbolic details. Important 20th-century stained glass artists include John Hayward, Douglas Strachan, Ervin Bossanyi, Louis Davis, Wilhelmina Geddes, Karl Parsons, John Piper, Patrick Reyntiens, Johannes Schreiter, Brian Clarke, Paul Woodroffe, Jean René Bazaine at Saint Séverin, Sergio de Castro at Couvrechef- La Folie (Caen), Hamburg-Dulsberg and Romont (Switzerland), and the Loire Studio of Gabriel Loire at Chartres. The west windows of England's Manchester Cathedral, by Tony Hollaway, are some of the most notable examples of symbolic work.

In Germany, stained glass development continued with the inter-war piece of work of Johan Thorn Prikker and Josef Albers, and the postal service-war achievements of Joachim Klos, Johannes Schreiter and Ludwig Shaffrath. This grouping of artists, who advanced the medium through the abandonment of figurative designs and painting on glass in favour of a mix of biomorphic and rigorously geometric abstraction, and the calligraphic non-functional use of leads,[32] are described as having produced "the first authentic school of stained drinking glass since the Middle Ages".[33] The works of Ludwig Schaffrath demonstrate the late 20th-century trends in the use of stained drinking glass for architectural purposes, filling unabridged walls with coloured and textured glass. In the 1970s young British stained-drinking glass artists such every bit Brian Clarke were influenced by the large scale and abstraction in German language twentieth-century glass.[32]

In the UK, the professional organization for stained glass artists has been the British Guild of Chief Drinking glass Painters, founded in 1921. Since 1924 the BSMGP has published an annual journal, The Journal of Stained Glass. It continues to be Britain'due south only organisation devoted exclusively to the fine art and craft of stained glass. From the outset, its principal objectives have been to promote and encourage high standards in stained glass painting and staining, to act as a locus for the exchange of data and ideas inside the stained glass craft and to preserve the invaluable stained glass heritage of Britain. See www.bsmgp.org.uk for a range of stained glass lectures, conferences, tours, portfolios of recent stained drinking glass commissions by members, and information on courses and the conservation of stained glass. Back bug of The Journal of Stained Drinking glass are listed and there is a searchable index for stained glass articles, an invaluable resources for stained glass researchers.

Afterwards the First World War, stained glass window memorials were a popular pick amidst wealthier families, examples can be institute in churches beyond the UK.

In the United States, there is a 100-year-old trade system, The Stained Glass Clan of America, whose purpose is to office as a publicly recognized system to assure survival of the craft by offering guidelines, instruction and training to craftspersons. The SGAA likewise sees its office equally defending and protecting its arts and crafts confronting regulations that might restrict its freedom as an architectural art course. The current president is Kathy Bernard. Today there are academic establishments that teach the traditional skills. Ane of these is Florida State University's Primary Craftsman Program, which recently completed a 30 ft (nine.i thou) high stained-glass windows, designed past Robert Bischoff, the program's manager, and Jo Ann, his wife and installed to overlook Bobby Bowden Field at Doak Campbell Stadium. The Roots of Knowledge installation at Utah Valley University in Orem, Utah is 200 feet (61 m) long and has been compared to those in several European cathedrals, including the Cologne Cathedral in Germany, Sainte-Chapelle in French republic, and York Minster in England.[34]

-

-

Thin slices of agate set into lead and glass, Grossmünster, Zürich, Switzerland, by Sigmar Polke (2009)

Combining ancient and modernistic traditions [edit]

-

Mid-20th-century window showing a continuation of ancient and 19th-century methods applied to a modern historical subject. Florence Nightingale window at St Peters, Derby, made for the Derbyshire Royal Infirmary

-

Figurative blueprint using the lead lines and minimal glass paint in the 13th-century manner combined with the texture of Cathedral glass, Ins, Switzerland

-

St Michael and the Devil at the church of St Michael Paternoster Row, by English creative person John Hayward combines traditional methods with a distinctive use of shard-like sections of glass.

Buildings incorporating stained glass windows [edit]

Churches [edit]

Stained glass windows were commonly used in churches for decorative and informative purposes. Many windows are donated to churches by members of the congregation equally memorials of loved ones. For more than information on the employ of stained drinking glass to describe religious subjects, see Poor Human's Bible.

- Important examples

- Cathedral of Chartres, in French republic, 11th- to 13th-century glass

- Canterbury Cathedral, in England, 12th to 15th century plus 19th- and 20th-century glass

- York Minster, in England, 11th- to 15th-century glass

- Sainte-Chapelle, in Paris, 13th- and 14th-century glass

- Florence Cathedral, Italian republic, 15th-century drinking glass designed past Uccello, Donatello and Ghiberti

- St. Andrew's Cathedral, Sydney, Commonwealth of australia, early consummate bicycle of 19th-century drinking glass, Hardman of Birmingham.

- Fribourg Cathedral, Switzerland, complete bicycle of glass 1896–1936, past Józef Mehoffer

- Coventry Cathedral, England, mid-20th-century glass by diverse designers, the large baptistry window beingness by John Piper

- Dark-brown Memorial Presbyterian Church building, all-encompassing collection of windows by Louis Comfort Tiffany

Synagogues [edit]

In add-on to Christian churches, stained glass windows have been incorporated into Jewish temple architecture for centuries. Jewish communities in the United States saw this emergence in the mid-19th century, with such notable examples as the sanctuary depiction of the Ten Commandments in New York's Congregation Anshi Chesed. From the mid-20th century to the nowadays, stained glass windows have been a ubiquitous feature of American synagogue compages. Styles and themes for synagogue stained drinking glass artwork are equally diverse every bit their church counterparts. As with churches, synagogue stained glass windows are ofttimes defended by member families in exchange for major financial contributions to the institution.

Places of worship [edit]

-

Interior of the Blue Mosque, Istanbul.

-

Stained glass windows in the Mosque of Srinagar, Kashmir

-

-

-

Tardily 20th-century stained glass from Temple Ohev Sholom, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania by Ascalon Studios.

-

Mausolea [edit]

Mausolea, whether for full general community employ or for individual family use, may utilize stained glass equally a comforting entry for natural light, for memorialization, or for display of religious imagery.

-

-

Stained-glass window in the Benedum mausoleum, Homewood Cemetery, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

Houses [edit]

Stained glass windows in houses were particularly popular in the Victorian era and many domestic examples survive. In their simplest form they typically describe birds and flowers in small panels, often surrounded with auto-fabricated cathedral glass which, despite what the proper noun suggests, is pale-coloured and textured. Some large homes have splendid examples of secular pictorial drinking glass. Many small houses of the 19th and early 20th centuries accept leadlight windows.

- Prairie style homes

- The houses of Frank Lloyd Wright

-

-

Sliding pantry door installed in a suburban home.

Public and commercial buildings [edit]

Stained glass has often been used as a decorative chemical element in public buildings, initially in places of learning, government or justice but increasingly in other public and commercial places such as banks, retailers and railway stations. Public houses in some countries make extensive apply of stained glass and leaded lights to create a comfortable atmosphere and retain privacy.

-

Stained drinking glass in the Town Hall, Liberec, Czech Democracy

-

Sculpture [edit]

-

Fused drinking glass sculpture (2012) by Carlo Roccella [fr] Glass Sculpture in Paris. France

See also [edit]

- Architectural glass

- Compages of cathedrals and great churches

- Fine art Nouveau glass

- Autonomous stained glass

- Askew glass

- British and Irish stained drinking glass (1811–1918)

- English Gothic stained glass windows

- French Gothic stained drinking glass windows

- Float glass

- Drinking glass beadmaking

- Sagrada (board game)

- Stained glass conservation

- Studio glass

- Suncatcher

- Venetian drinking glass

- Window

References [edit]

- ^ "Stained Glass in Medieval Europe". Department of Medieval Fine art and The Cloisters. The Metropolitain Museum of Art. Retrieved 13 June 2019.

- ^ "Facts about Glass – Creating Coloured Drinking glass; Pot-metal glass", Boppard Conservation Project – Glasgow Museums

- ^ Investigations in Medieval Stained Glass: Materials, Methods, and Expressions, xvii, eds., Brigitte Kurmann-Schwarz, Elizabeth Pastan, 2019, BRILL, ISBN 9004395717, 9789004395718, google books

- ^ "Facts about Drinking glass: Early Drinking glass Painting", Boppard Conservation Project – Glasgow Museums; Historic England, 287-288

- ^ Barbara Butts, Lee Hendrix and others, Painting on Light: Drawings and Stained Drinking glass in the Historic period of Dürer and Holbein, 183, 2001, Getty Publications, ISBN 089236579X, ISBN 9780892365791, google books

- ^ Steinhoff, Frederick Louis (1973). Ceramic Industry. Industrial Publications, Incorporated.

- ^ Chambers's encyclopaedia. Pergamon Press. 1967.

- ^ "Facts near Glass: Silvery Stain", Boppard Conservation Project – Glasgow Museums; Historic England, 290

- ^ Modern Methods for Analysing Archaeological and Historical Glass, section vii.iii.three.v, 2013, ed. Koen H. A. Janssens, Wiley, ISBN 1118314204, 9781118314203, google books

- ^ In fact Jean Cousin the Elder was only born in 1500, at the aforementioned time as the tehnique; claims that he was the commencement French painter in oils might be more valid.

- ^ "Facts about Glass: Sanguine and Carnation", Boppard Conservation Project – Glasgow Museums; Historic England, 288

- ^ a b Celebrated England, 290

- ^ "Examples of Writing in Stained Glass", Boppard Conservation Project – Glasgow Museums

- ^ a b Illustrated Glass Lexicon world wide web.glassonline.com. Retrieved 3 August 2006

- ^ Chemical Fact Sail – Chromium Archived 15 August 2017 at the Wayback Motorcar www.speclab.com. Retrieved 3 August 2006

- ^ a b Geary, Theresa Flores (2008). The Illustrated Bead Bible: Terms, Tips & Techniques. Sterling Publishing Company, Inc. p. 108. ISBN9781402723537.

- ^ Substances Used in the Making of Coloured Glass 1st.glassman.com (David M Issitt). Retrieved three Baronial 2006

- ^ Uranium Glass www.glassassociation.org.uk (Barrie Skelcher). Retrieved 3 August 2006

- ^ "Facts nearly glass: Assembling a stained-drinking glass panel", Boppard Conservation Project – Glasgow Museums

- ^ Discovering stained drinking glass – John Harries, Carola Hicks, Edition: 3 – 1996

- ^ Ahmad Y Hassan, The Manufacture of Coloured Glass and Cess of Kitab al-Durra al-Maknuna, History of Science and Technology in Islam.

- ^ Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ "Fairford Church". Sacred-destinations.com. 20 October 2007. Retrieved 24 March 2014.

- ^ a b Lee, Seddon and Stephens, pp. 118–121

- ^ a b Vidimus, Dirck Peterz. Crabeth Archived 30 July 2014 at the Wayback Machine Issue 20 (accessed 26 Baronial 2012)

- ^ a b c Gordon Campbell, The Grove Encyclopedia of Decorative Arts, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-518948-5

- ^ a b Peter Cormack, Arts & Crafts Stained Glass, Yale University Press, 2015

- ^ "Joining drinking glass mosaics".

- ^ "Le yard dictionnaire Québec regime's online dictionary entry for gemmail (in French)". eight April 2003. Archived from the original on 2 April 2003. Retrieved 24 March 2014.

- ^ Gemmail, Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ [1], Gemmail Fourth dimension

- ^ a b Harrod, Tanya, The Crafts in Britain in the 20th Century, Yale Academy Press (4 Feb 1999), ISBN 978-0300077803, p. 452

- ^ "Stained glass: 20th century". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.

- ^ O'Hear, Natasha (eight December 2016). "History illuminated: The evolution of noesis told through 60,000 pieces of glass". CNN.com. Archived from the original on 20 April 2017. Retrieved 19 April 2017.

- "Celebrated England" = Applied Building Conservation: Glass and glazing, by Celebrated England, 2011, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., ISBN 0754645576, 9780754645573, google books

Farther reading [edit]

- Martin Harrison, 'Victorian Stained Drinking glass', Barrie & Jenkins, 1980 ISBN 0214206890

- The Journal of Stained Drinking glass, Burne-Jones Special Upshot, Vol. XXXV, 2011 ISBN 978 0 9568762 1 eight

- The Journal of Stained Glass, Scotland Issue, Vol. XXX, 2006 ISBN 978 0 9540457 6 0

- The Journal of Stained Glass, Special Effect, The Stained Drinking glass Drove of Sir John Soane's Museum, Vol. XXVII, 2003 ISBN 0 9540457 3 4

- The Journal of Stained Glass, America Outcome, Vol. XXVIII, 2004 ISBN 0 9540457 4 2

- Peter Cormack, 'Arts & Crafts Stained Glass', Yale University Press, 2015 ISBN 978-0-300-20970-nine

- Caroline Swash, 'The 100 All-time Stained Glass Sites in London', Malvern Arts Printing, 2015 ISBN 978-0-9541055-2-5

- Nicola Gordon Bowe, 'Wilhelmina Geddes, Life and Piece of work', 4 Courts Press, 2015 ISBN 978-1-84682-532-3

- Lucy Costigan & Michael Cullen (2010). Strangest Genius: The Stained Glass of Harry Clarke, The History Press, Dublin, ISBN 978-i-84588-971-5

- Theophilus (ca 1100). On Divers Arts, trans. from Latin by John G. Hawthorne and Cyril Stanley Smith, Dover, ISBN 0-486-23784-2

- Elizabeth Morris (1993). Stained and Decorative Glass, Tiger Books, ISBN 0-86824-324-eight

- Sarah Brown (1994). Stained Glass- an Illustrated History, Bracken Books, ISBN 1-85891-157-five

- Painton Cowen (1985). A Guide to Stained Drinking glass in Britain, Michael Joseph, ISBN 0-7181-2567-3

- Husband, TB, The Luminous Image: Painted Glass Roundels in the Lowlands, 1480-1560, 2000, Metropolitan Museum of Fine art

- Lawrence Lee, George Seddon, Francis Stephens (1976).Stained Glass, Mitchell Beazley, ISBN 0-600-56281-6

- Simon Jenkins (2000). England'due south Thousand Best Churches, Penguin, ISBN 0-7139-9281-6

- Robert Eberhard. Database: Church Stained Drinking glass Windows.

- Cliff and Monica Robinson. Database: Buckinghamshire Stained Glass.

- Stained Glass Association of America. History of Stained Drinking glass.

- Robert Kehlmann (1992). 20th Century Stained Glass: A New Definition, Kyoto Shoin Co., Ltd., Kyoto, ISBN iv-7636-2075-four

- Kisky, Hans (1959). 100 Jahre Rheinische Glasmalerei, Neuss : Verl. Gesellschaft für Buchdruckerei, OCLC 632380232

- Robert Sowers (1954). The Lost Fine art, George Wittenborn Inc., New York, OCLC 1269795

- Robert Sowers (1965). Stained Glass: An Architectural Art, Universe Books, Inc., New York, OCLC 21650951

- Robert Sowers (1981). The Language of Stained Drinking glass, Timber Printing, Forest Grove, Oregon, ISBN 0-917304-61-6

- Hayward, Jane (2003). English language and French medieval stained glass in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN1872501370.

- Virginia Chieffo Raguin (2013). Stained Drinking glass: Radiant Art . Los Angeles: Getty Publications. ISBN978-1606061534.

- Conrad Rudolph, "Inventing the Exegetical Stained-Drinking glass Window: Suger, Hugh, and a New Elite Art," Fine art Bulletin 93 (2011) 399–422

- Conrad Rudolph, "The Parabolic Discourse Window and the Canterbury Gyre: Social Modify and the Exclamation of Elite Status at Canterbury Cathedral," Oxford Fine art Journal 38 (2015) 1–19

External links [edit]

- BSMGP | The home of British Stained Glass

- SGAA Sourcebook Find a Studio - The Stained Glass Association of America

- Preservation of Stained Glass

- Church building Stained Glass Window Database recorded by Robert Eberhard, covering ≈2800 churches in the southeast of England

- Institute for Stained Glass in Canada, over 10,000 photos; a multi-year photographic survey of Canada's stained glass from many countries; 1856 to present

- The Stained Glass Museum (Ely, England)

- Vitromusée Romont (Romont (FR), Switzerland)

- Stained glass workshops (Uk)

- Stained glass guide (Uk)

- "Stained Glass". Glass. Victoria and Albert Museum. Archived from the original on 23 December 2012. Retrieved 16 June 2007.

- Gloine – Stained glass in the Church building of Republic of ireland Inquiry carried out by Dr David Lawrence on behalf of the Representative Church building Torso of the Church building of Ireland, partially funded past the Heritage Quango

- Stained-glass windows by Sergio de Castro in France, Germany and Switzerland

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stained_glass

0 Response to "what were many of the stained glass windows of the middle ages meant to do"

Post a Comment